Peter Maverick and His Family - No. 3, Crown Street · The Early Mavericks · The Young Engraver · The Independent Engraver · Country Squire and Teacher · Maverick and Durand · Maverick's Last Years · The Maverick Name and Engraving

Review

Any serious student concerned with American history from the latter part of the 18th century through the first quarter of the 19th century is bound to run across the name of Maverick, either in connection with book illustrations, book plates, maps, certificates, portraits, trade cards or on occasion a town view. This book, in a systematic way, presents the many members of the Maverick family who were actively engaged in various forms of engraving and lithography: Peter Rushton Maverick, 1755-1811; his son, Peter, 1780-1831, by far the most productive member of the family; Peter's brother Samuel, 1789-1845; and finally Peter, Jr., 1809-1845, lithographer, to mention a few of the better known members of the family. Among the minor print-making members of the family were the four daughters of Peter, as well as Ann, the daughter of Dr. Alexander Anderson, who married Andrew, son of the printmaking Andrew, brother of Peter and Samuel. The text covering eighty pages is smoothly written although it is rather dull. It is based on vital statistics cemented together by a mixture of historical background and a great amount of surmise.

To sum up the book, it may be said that Mr. Stephens, who is a professor of English at Rutgers University, has painstakingly expanded Stauffer and that the author's chief concern in preparing the catalogue, with its great bulk of ephemera, is in the ephemera itself. What then, may be asked, is Mr. Stephens' contribution to the history of American art? The answer apparently is that Mr. Stephens has failed to prove that any member of the family made any important mark. Peter Maverick, despite his great excellence in bank note engraving, to judge from the examples illustrated in this book, hardly would be noticed in the overall picture when a good comprehensive history of American art is written. Not that the author has failed to do a good job of research, for he has. But in his searching and studying of the many Maverick prints, he has not given us any assurance or proof that the Maverick contribution was actually worthy of such an effort as he has put into this present volume.

Smith College Museum of Art

Any serious student concerned with American history from the latter part of the 18th century through the first quarter of the 19th century is bound to run across the name of Maverick, either in connection with book illustrations, book plates, maps, certificates, portraits, trade cards or on occasion a town view. This book, in a systematic way, presents the many members of the Maverick family who were actively engaged in various forms of engraving and lithography: Peter Rushton Maverick, 1755-1811; his son, Peter, 1780-1831, by far the most productive member of the family; Peter's brother Samuel, 1789-1845; and finally Peter, Jr., 1809-1845, lithographer, to mention a few of the better known members of the family. Among the minor print-making members of the family were the four daughters of Peter, as well as Ann, the daughter of Dr. Alexander Anderson, who married Andrew, son of the printmaking Andrew, brother of Peter and Samuel. The text covering eighty pages is smoothly written although it is rather dull. It is based on vital statistics cemented together by a mixture of historical background and a great amount of surmise.

To sum up the book, it may be said that Mr. Stephens, who is a professor of English at Rutgers University, has painstakingly expanded Stauffer and that the author's chief concern in preparing the catalogue, with its great bulk of ephemera, is in the ephemera itself. What then, may be asked, is Mr. Stephens' contribution to the history of American art? The answer apparently is that Mr. Stephens has failed to prove that any member of the family made any important mark. Peter Maverick, despite his great excellence in bank note engraving, to judge from the examples illustrated in this book, hardly would be noticed in the overall picture when a good comprehensive history of American art is written. Not that the author has failed to do a good job of research, for he has. But in his searching and studying of the many Maverick prints, he has not given us any assurance or proof that the Maverick contribution was actually worthy of such an effort as he has put into this present volume.

Smith College Museum of Art

MARY BARTLETT COWDREY

PETER MAVERICK

& HIS FAMILY

No. 3, Crown Street

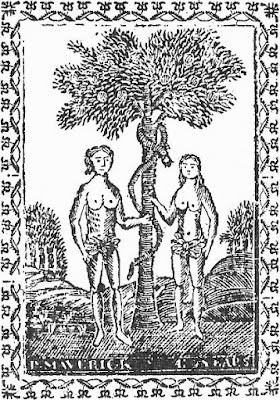

Liberty Street in lower Manhattan Island in the late eighteenth century—before the new American consciousness had turned to the task of purging the nation of inappropriate geographical terms—was named in proper loyalty Crown Street. At No. 3, near the eastern end where it meets Maiden Lane, soon after these newly united states had set up their first offices and installed their first president in the refitted municipal building on Wall Street a few blocks south, a nine-year-old boy was busy in the shop of his father. Before him on his bench was a printing block. To it had been transferred a drawing—a small simple drawing of a tree and a serpent and a man and a woman, the age-old picture of Adam and Eve. Under the boy's hand was an engraver's burin, a steel tool with a point like a tiny plow, which can turn up a curl of soft metal or end-grain wood in strokes light or heavy as the engraver's hand and wrist may direct. With this tool the boy was at work preparing the block for printing, cutting from its surface all that which should be white in the final picture, and leaving untouched the other parts, the lines and dots and dark areas which should press the ink upon the paper in the final printing.

The proprietor of the shop came from time to time to encourage his son, leaving for a moment the copperplate which he himself was preparing. Copperplate work, with which the shop was chiefly concerned, involved a quite different process from that in which the boy was destined to make his fame. Sometimes, too, the father's assistant, perhaps a relative [The U.S. census of 1790 records one man as a member of the household who was not listed as an employee nor as a member of the immediate family.], or an apprentice who had been indentured for training in the craft of engraving or silversmithing, would look with half condescension and half awe at this child whose hand seemed already almost skillful, whose discrimination seemed already almost sure.

It was a good shop. Here were to be found copperplates and type-metal blocks, and burins and supplies of all sorts for professional or amateur engravers. To this shop, after studying art in the studios of Europe, had come the actor and painter, William Dunlap, to learn the "theory and practice of etching," and to etch and print the frontpiece for a dramatic publication then occupying his mind. Years later this versatile artist made special mention of the adequacy of the shop, and his opinion was that of a discriminating judge. Here too, to echo newspaper announcements of the owner, men came to have their coats of arms engraved, and women to have their tea-table silver decorated, and all would be done as well, said the shopmaster in his enthusiasm for the new nation, as could be done in Europe. With what pride the maker of that boast must have received, the year before, the order from James Duane to provide a silver seal for the new United States District Court and to engrave on it the figure of Liberty, or the order from a neighboring institution of learning to remove the name of King's College from its seal and inlay a plate with the name Colombia.

The boy had already cut carefully around the outline of his design and had routed out enough of his large white areas to know which of the remaining areas were trees and hills and figures. The large central tree offered an attractive task. Holding the tool with a light steady pressure, he moved tool and block in a circular movement to outline the apples, and then, as his father had instructed him, he covered the curved surfaces of the apples with short rounded strokes, varying the direction that the apples might not seem to blend too much with the foliage. The foliage itself was easy, for after the edge of the area had been cut like the edge of a saw, he had merely to repeat over and over again the quick curved stroke that suggested leaf shapes. In the part of the tree above Eve he seems to have become careless, or perhaps his hands became tired of repeating the same stroke, but just above Adam his burin again moved with sureness, for the lines are clean and firm. Let us hope that his father praised him a little for that spot of clean cutting! [It is, of course, possible that it was the father who cut the spot in showing the boy how to do it.]

But the tree trunk and the serpent were left, and both were cylindrical objects. So the boy, according to his instructions, cut strokes across each, strokes with a slight curve to suggest the surface, strokes minutely drawn from the top of the trunk to the spreading root, from the head of the snake to the curiously broken tip of its tail. But what happened to that tail? Did a routing tool slip while the white area was being cleared, and thus suddenly change the tail's direction?

The background demanded only variations of the techniques required for the tree; the strokes for the foliage, of course, were smaller and lighter. When the effect seemed too much like that of a single tree on each side of the central group, a few vertical strokes of the burin separated the trees and moved them back to where they belonged. To keep them there, the boy accentuated the rolling hills in front of the woods, varying the direction of the curving strokes to mark each rise. But Adam and Eve are standing on no such varied surfaces; here the strokes are straight, with a change of their direction as the foreground approaches the eye of the spectator.

Of course the boy did not learn how to do all this as he cut this particular block. Under his father's direction he had been drawing pictures and cutting blocks for a long time, studying especially how to establish this or that effect with black pencil lines on white paper. In this engraving he treated the hills and the foreground in much the same way as he had learned to produce such an effect with a pencil; as long as he was dealing with close parallel lines, it mattered little whether he drew the black lines or cut out the white ones.

But the human figures presented problems. Here his tool must leave the black surface untouched, and the strokes of its cutting edge must be made where the final picture was to be white. The surfaces on body and limbs and face which were in shadow had to be left untouched, the areas in full light had to be cut away. The boy took no chances with the faces; except for suggesting a little stubble on Adam's cheek and chin, he shows the features in outline only, and in the noses of Adam and Eve the outline reaches a minimum which might be called perfection. The boy's hand must have moved carefully to leave these shaped dots untouched on the surface.

But he was not satisfied to make of the whole picture a mere outline drawing; after clearly marking off bodies and arms and legs (notice the knees) he worked for highlights and shadows. With Eve he adopted the traditional source of light, a point above and to the left of the picture, and he shaded consistently. With Adam, however, his sense of symmetry and balance must have overcome his feeling for the source of light, and he shaded as if the light or—as some of the devout who were shocked by his father's religious views might have been glad to say—from the serpent. Whatever the source, Adam's right leg, from the knee down, is unrecipient to that light, and has a source of its own somewhere over at the left.

With these problems met, and the shadows softened with light strokes to relieve their blackness, the bowknots of fig leaves—or whatever their substance is—were carefully cut. One speculates as to where the boy found a model for those garments, for they are strangely reminiscent of the garments worn by two figures in a bookplate which his father had recently made for P. J. Van Berckell.

On an untouched strip which remained at the bottom, the boy cut the signature which he was later to learn to cut with confidence and skill in plates of many kinds. On the straight lines he cut boldly, varying the broad and the narrow strokes according to intention. The intial P is accomplished, the M is well passed, the A is fumbled a little at the top but the V redeems it, and the E deserves special praise. The R demanded curves, however, and although they are executed with a fine sweep, the lines are weak; perhaps he decided not to fatten them and risk a worse flaw. The I and C and K go swimmingly, although the curves of C appear to have presented some hazards. But on the small Sct., written as his father wrote it with the t raised above the line, his boldness evidently waned; the curves are cut with a hesitant hand, with the surface of the block scratched scarcely enough to show in the print.

Confidence seems to have returned with the capital letters in the linked Æ and to remain with him for the most part in the word YEARS, carrying him fairly well through the curves of R but failing him on the tricky S at the end. But immediately above the Æ (which his father had explained was the abbreviation of the Latin for aged, as Sct. was for engraved), in cutting the figure 9 his confidence deserted him completely; he seems first to have scratched in a hasty figure, and then to have tried to correct it by scratching again, as if stricken with a sudden shock at his own presumption in preparing a cut for publication at such an age.

But it was published. With an ornamental border of type and with an explanatory quotation from Genesis below it, it had the place of honor as the frontpiece of The Holy Bible Abridged, published by Hodge, Allen, and Campbell in New York in 1790. We have evidence that the father and master of the shop, Peter Rushton Maverick, was proud of his promising son and pupil. The boy's mother had died three years before, but his new stepmother, his mother's sister, probably also approved the youngster's progress and wished the like, or better, for her own baby Samuel. Seven-year-old Andrew and five-year-old Maria perhaps realized little what the excitement meant, but big sisters Sarah and Rebecca and Ann could have appreciated his work and given the oldest of their brothers the praise that was due him, for there are many evidences of close and friendly family ties.

It was a humble family, and none of its members recorded for posterity its thoughts, opinions, or deeds. The very few letters that exist today were kept chiefly because they were written to prominent people, not because they were from people that were worth remembering. The only record of their births was in the family Bible and perhaps in the baptismal record of some church. When they married, the Bible and the civil and church records again recorded the fact. At their deaths the newspapers ran no obituary, but listed as briefly as possible the age, the cause of death, and the hour and place of the funeral services. They were businessmen and craftsmen in a large city which did not find in an industrious worker in his craft a person of special importance.

But the family was proud of itself and kept a record of its members. Moreover, these members left records when they bought land and sold it, or gave mortgages and had them foreclosed. They qualified as freemen of the city and served in the militia. They joined churches and lodges and reform and mutual-aid societies; they signed petitions; they made contracts and wills; they testified in court proceedings. And they made engravings—for all kinds of purposes—to which they proudly attached their signatures. These engravings, hundreds of them, tell a story of the development of an American family and its craftsmanship which is as valid as if documented throughout by contemporary written opinion.

It was from such source materials as these that this biographical sketch has been built, and from them we know that between October 22, 1789, and the same date in 1790, the childhood triumph related above took place at No. 3, Crown Street.

& HIS FAMILY

No. 3, Crown Street

Liberty Street in lower Manhattan Island in the late eighteenth century—before the new American consciousness had turned to the task of purging the nation of inappropriate geographical terms—was named in proper loyalty Crown Street. At No. 3, near the eastern end where it meets Maiden Lane, soon after these newly united states had set up their first offices and installed their first president in the refitted municipal building on Wall Street a few blocks south, a nine-year-old boy was busy in the shop of his father. Before him on his bench was a printing block. To it had been transferred a drawing—a small simple drawing of a tree and a serpent and a man and a woman, the age-old picture of Adam and Eve. Under the boy's hand was an engraver's burin, a steel tool with a point like a tiny plow, which can turn up a curl of soft metal or end-grain wood in strokes light or heavy as the engraver's hand and wrist may direct. With this tool the boy was at work preparing the block for printing, cutting from its surface all that which should be white in the final picture, and leaving untouched the other parts, the lines and dots and dark areas which should press the ink upon the paper in the final printing.

The proprietor of the shop came from time to time to encourage his son, leaving for a moment the copperplate which he himself was preparing. Copperplate work, with which the shop was chiefly concerned, involved a quite different process from that in which the boy was destined to make his fame. Sometimes, too, the father's assistant, perhaps a relative [The U.S. census of 1790 records one man as a member of the household who was not listed as an employee nor as a member of the immediate family.], or an apprentice who had been indentured for training in the craft of engraving or silversmithing, would look with half condescension and half awe at this child whose hand seemed already almost skillful, whose discrimination seemed already almost sure.

It was a good shop. Here were to be found copperplates and type-metal blocks, and burins and supplies of all sorts for professional or amateur engravers. To this shop, after studying art in the studios of Europe, had come the actor and painter, William Dunlap, to learn the "theory and practice of etching," and to etch and print the frontpiece for a dramatic publication then occupying his mind. Years later this versatile artist made special mention of the adequacy of the shop, and his opinion was that of a discriminating judge. Here too, to echo newspaper announcements of the owner, men came to have their coats of arms engraved, and women to have their tea-table silver decorated, and all would be done as well, said the shopmaster in his enthusiasm for the new nation, as could be done in Europe. With what pride the maker of that boast must have received, the year before, the order from James Duane to provide a silver seal for the new United States District Court and to engrave on it the figure of Liberty, or the order from a neighboring institution of learning to remove the name of King's College from its seal and inlay a plate with the name Colombia.

The boy had already cut carefully around the outline of his design and had routed out enough of his large white areas to know which of the remaining areas were trees and hills and figures. The large central tree offered an attractive task. Holding the tool with a light steady pressure, he moved tool and block in a circular movement to outline the apples, and then, as his father had instructed him, he covered the curved surfaces of the apples with short rounded strokes, varying the direction that the apples might not seem to blend too much with the foliage. The foliage itself was easy, for after the edge of the area had been cut like the edge of a saw, he had merely to repeat over and over again the quick curved stroke that suggested leaf shapes. In the part of the tree above Eve he seems to have become careless, or perhaps his hands became tired of repeating the same stroke, but just above Adam his burin again moved with sureness, for the lines are clean and firm. Let us hope that his father praised him a little for that spot of clean cutting! [It is, of course, possible that it was the father who cut the spot in showing the boy how to do it.]

But the tree trunk and the serpent were left, and both were cylindrical objects. So the boy, according to his instructions, cut strokes across each, strokes with a slight curve to suggest the surface, strokes minutely drawn from the top of the trunk to the spreading root, from the head of the snake to the curiously broken tip of its tail. But what happened to that tail? Did a routing tool slip while the white area was being cleared, and thus suddenly change the tail's direction?

The background demanded only variations of the techniques required for the tree; the strokes for the foliage, of course, were smaller and lighter. When the effect seemed too much like that of a single tree on each side of the central group, a few vertical strokes of the burin separated the trees and moved them back to where they belonged. To keep them there, the boy accentuated the rolling hills in front of the woods, varying the direction of the curving strokes to mark each rise. But Adam and Eve are standing on no such varied surfaces; here the strokes are straight, with a change of their direction as the foreground approaches the eye of the spectator.

Of course the boy did not learn how to do all this as he cut this particular block. Under his father's direction he had been drawing pictures and cutting blocks for a long time, studying especially how to establish this or that effect with black pencil lines on white paper. In this engraving he treated the hills and the foreground in much the same way as he had learned to produce such an effect with a pencil; as long as he was dealing with close parallel lines, it mattered little whether he drew the black lines or cut out the white ones.

But the human figures presented problems. Here his tool must leave the black surface untouched, and the strokes of its cutting edge must be made where the final picture was to be white. The surfaces on body and limbs and face which were in shadow had to be left untouched, the areas in full light had to be cut away. The boy took no chances with the faces; except for suggesting a little stubble on Adam's cheek and chin, he shows the features in outline only, and in the noses of Adam and Eve the outline reaches a minimum which might be called perfection. The boy's hand must have moved carefully to leave these shaped dots untouched on the surface.

But he was not satisfied to make of the whole picture a mere outline drawing; after clearly marking off bodies and arms and legs (notice the knees) he worked for highlights and shadows. With Eve he adopted the traditional source of light, a point above and to the left of the picture, and he shaded consistently. With Adam, however, his sense of symmetry and balance must have overcome his feeling for the source of light, and he shaded as if the light or—as some of the devout who were shocked by his father's religious views might have been glad to say—from the serpent. Whatever the source, Adam's right leg, from the knee down, is unrecipient to that light, and has a source of its own somewhere over at the left.

With these problems met, and the shadows softened with light strokes to relieve their blackness, the bowknots of fig leaves—or whatever their substance is—were carefully cut. One speculates as to where the boy found a model for those garments, for they are strangely reminiscent of the garments worn by two figures in a bookplate which his father had recently made for P. J. Van Berckell.

On an untouched strip which remained at the bottom, the boy cut the signature which he was later to learn to cut with confidence and skill in plates of many kinds. On the straight lines he cut boldly, varying the broad and the narrow strokes according to intention. The intial P is accomplished, the M is well passed, the A is fumbled a little at the top but the V redeems it, and the E deserves special praise. The R demanded curves, however, and although they are executed with a fine sweep, the lines are weak; perhaps he decided not to fatten them and risk a worse flaw. The I and C and K go swimmingly, although the curves of C appear to have presented some hazards. But on the small Sct., written as his father wrote it with the t raised above the line, his boldness evidently waned; the curves are cut with a hesitant hand, with the surface of the block scratched scarcely enough to show in the print.

Confidence seems to have returned with the capital letters in the linked Æ and to remain with him for the most part in the word YEARS, carrying him fairly well through the curves of R but failing him on the tricky S at the end. But immediately above the Æ (which his father had explained was the abbreviation of the Latin for aged, as Sct. was for engraved), in cutting the figure 9 his confidence deserted him completely; he seems first to have scratched in a hasty figure, and then to have tried to correct it by scratching again, as if stricken with a sudden shock at his own presumption in preparing a cut for publication at such an age.

But it was published. With an ornamental border of type and with an explanatory quotation from Genesis below it, it had the place of honor as the frontpiece of The Holy Bible Abridged, published by Hodge, Allen, and Campbell in New York in 1790. We have evidence that the father and master of the shop, Peter Rushton Maverick, was proud of his promising son and pupil. The boy's mother had died three years before, but his new stepmother, his mother's sister, probably also approved the youngster's progress and wished the like, or better, for her own baby Samuel. Seven-year-old Andrew and five-year-old Maria perhaps realized little what the excitement meant, but big sisters Sarah and Rebecca and Ann could have appreciated his work and given the oldest of their brothers the praise that was due him, for there are many evidences of close and friendly family ties.

It was a humble family, and none of its members recorded for posterity its thoughts, opinions, or deeds. The very few letters that exist today were kept chiefly because they were written to prominent people, not because they were from people that were worth remembering. The only record of their births was in the family Bible and perhaps in the baptismal record of some church. When they married, the Bible and the civil and church records again recorded the fact. At their deaths the newspapers ran no obituary, but listed as briefly as possible the age, the cause of death, and the hour and place of the funeral services. They were businessmen and craftsmen in a large city which did not find in an industrious worker in his craft a person of special importance.

But the family was proud of itself and kept a record of its members. Moreover, these members left records when they bought land and sold it, or gave mortgages and had them foreclosed. They qualified as freemen of the city and served in the militia. They joined churches and lodges and reform and mutual-aid societies; they signed petitions; they made contracts and wills; they testified in court proceedings. And they made engravings—for all kinds of purposes—to which they proudly attached their signatures. These engravings, hundreds of them, tell a story of the development of an American family and its craftsmanship which is as valid as if documented throughout by contemporary written opinion.

It was from such source materials as these that this biographical sketch has been built, and from them we know that between October 22, 1789, and the same date in 1790, the childhood triumph related above took place at No. 3, Crown Street.

The Early Mavericks

Peter Maverick bore a surname which had long been a part of America's history, although there is little reason to believe that he was aware of the fact. His children and nephews a generation later apparently had a vague and completely erroneous idea that their grandfather Maverick had come "to this country from England, about the year 1774, when but eight or ten years of age." They suspected that the New York Mavericks had some connection with the Boston Mavericks but they could not establish the link, even when they understood that a legacy in the Bank of England was somehow at stake.

Sometime later, in 1894, a report in the New England Historical and Genealogical Register proved their suspicions to be correct; records published by the same journal in 1942 and 1943 for the first time made generally available the genealogical ramifications of the Massachusetts Maverick family.

The known genealogical line begins with a certain Robert Maverick of Devonshire who had a son Peter, a clergyman who flourished in the early years of Elizabeth's reign. Among his children was a Reverend John Maverick, baptized November 28, 1578, who went to Exeter College at Oxford in 1595, receiving his degree of Bachelor of Arts in 1599 and Master of Arts in 1603.

He served his church in Devonshire for years, and then in 1630 sailed with several of his family for Massachusetts, arriving at Hull on May 30 and proceeding thence to Dorchester. A year later he took the freeman's oath, and he lived as a colonist and leader of his church until his death in 1637, to be followed in that leadership by Richard, the first of Mathers.

Although Reverend John Maverick was the founder of the family in America, he was not the first of that family to arrive in this country. His young son Samuel had left England six years earlier and had settled on an island in Massachusetts Bay. In the new country he began a stormy career as a defender of the British crown against colonial discontent, a career which gave him the title of Loyalist, brought him an appointment as King's Commissioner, and earned him finally a royal gift of a house and lot at what is now 50 Broadway in New York.

There may have been another son of John, bearing his father's name, who went to the Barbadoes and later in life to the colony of Carolina, there to found the American family of Mavericks who have long been prominent in the South. That this John was a son of Reverend John, and a brother of Samuel the Loyalist, is entirely plausible, but careful genealogists seem unwilling to say that the link is established.

But our chief concern is with Elias, another son of Reverend John. Elias' marriage to Anne Harris in 1633 brought him five sons and six daughters. Paul, one of these children, married Jemimah, the daughter of Lieutenant John Smith. Paul and Jemimah were the parents of the John Maverick who became an importer of hard woods in Middle (now Hanover) Street in Boston, at the sign of the Cabinet and Chest of Drawers. Probably the most famous Boston Maverick was Samuel, the grandson of this John, who as a boy was killed in the Boston massacre. But it is John's son Andrew, the father of Peter Rushton Maverick, who attracts our particular attention.

Andrew was born in Boston February 4, 1729, and baptized five days later. How and where he spent the first twenty-four years of his life is unknown, but in 1753 we find him in New York City, where on July 17 he was admitted as a freeman. On March 28 of the following year he married eighteen-year-old Sarah Rushton, the daughter of the prosperous mason Peter Rushton, and four years later, on March 13, 1759, he joined Captain Tobias Van Zandt's company of New York militia. His occupation has been given by one writer as "painter," by another as "artist," but when he was admitted as a freeman and when he joined the militia, he himself designated his occupation as "painter." Except for a self-portrait which has been mentioned as his work, there appears to be little reason to consider him a worker in the fine arts.

There is one more record of Andrew before he slips from view in the obscurity of the scarce and poorly kept pre-Revolutionary records. In 1760, after George the Second died in England, the American colony elected a new assembly to represent the people to his young successor, George the Third. In New York City, there were six candidates, two of whom, James DeLancey and William Bayard, were eager to give the young king the same loyalty that they had given so profitably to his predecessor, while the other four, who were of the Whig or Patriot Party, represented the fast-growing national sentiment that was to bring revolt fifteen years later. During the three days of polling, in February of 1761, Andrew Maverick recorded his vote for the Patriots, Philip Livingston, William Cruger, John M. Scott, and Leonard Lispenard. Although Andrew did not live to see his only son, Peter Rushton Maverick, grow up, he left him this and other examples of independent thinking which the son was to follow energetically.

The early years of Peter Rushton Maverick are little illuminated by records, beyond that of his birth on April 11, 1755, and the death of his mother four years later. When the boy was ten, his grandfather Rushton made a will in which he left all his estate, including "houses, lands, bonds, slaves," to his wife Bethiah during her widowhood, but after her death the whole was to go to "my grandson Peter Rushton Maverick." From this and other provisions in the will it appears that Peter was not only an only child of his parents but also an only grandchild of the Rushtons, and the fact that no mention was made of Andrew may be the basis for the belief that he died before Peter's tenth birthday.

Two years after making this will the grandfather died. Bethiah lived on for twenty-three years longer, to see her grandson well established as an engraver and her great-grandson beginning his young apprenticeship. There appears to be no further record of the transfer of the family property to Maverick. Years afterward, however, when he sold the Rushton Liberty Street lot to the Quakers for a meeting house, he claimed his title to it as the "grandson and only heir" of Peter Rushton.

On July 4, 1772, the day not yet being a national holiday, seventeen-year-old Peter Rushton Maverick and nineteen-year-old Ann Reynolds posted bond with the secretary of the Province of New York and received a license to wed. Three years later, on Sunday, April 23, 1775, word of the battles of Concord and Lexington reached New York late in the day. Within forty-eight hours the royal arsenal had been sacked by the revolutionary mob and arms distributed among the revolutionary citizens. Peter, now a father as well as a husband, received a firelock, bayonet, belt, and other equipment; when he signed the receipt he wrote, as if in realization of the importance of the occasion, his full name, "Peter Rushton Maverick."

By midsummer, apparently to equip an organized body of militia, the weapons issued to the willing young men were recalled; and Maverick, described as a silversmith of Batteau (Dey) Street, was credited with Musket No. 543. This record gives us two bits of knowledge. It gives us Maverick's address nine years before the announcement in 1784 of his business in Crown Street. More important, it proves that Maverick was already established in his craft before the Revolution. The knowledge is not surprising, for an apt young man was scarcely likely to have been untrained at twenty, and he was, moreover, a man of family — baby Sarah was now a year and a half old, and another child was expected in the approaching winter.

Nearly a century ago the story was first recorded in print, without documentation, that by August of 1775 he was an ensign in Captain M. Minthorn's company of John Jay's Second Regiment of New York Militia, but there appears to be no official record. However, in 1789 after the Revolution had ended and the new nation had begun, the somewhat more mature Peter Rushton Maverick was listed as an ensign in Lieutenant Colonel James Alner's regiment, and four years later, in 1793, his title had become lieutenant.

When Rebecca, the second daughter of the Peter Rushton Mavericks, was born on January 8, 1776, New York was in constant threat of attack by the British. By 1778, the city was in the hands of the British Army, and about half of the population had fled to the Jerseys or to that part of New York above the Harlem River. Some of those who remained in the city stayed because they could not get away; many others stayed because their sympathies were with the established government. Did the Mavericks flee from New York at the threat of British attack? No record tells us, but, with a wife and two children to care for, it is hardly likely that Maverick would remain and risk British captivity.

Although three children were born to the Mavericks before the British evacuated New York in 1783, their places of birth are not recorded, and thus we have little or no clue as to the whereabouts of the family. We do know that a girl Ann was born on December 3, 1778, and a boy Peter was born October 22, 1780, and another boy Andrew on May 26, 1782. If the Mavericks were among the refugees from New York, then they must have returned very soon after the British left; the birthplace of a sixth child, Maria, who was born on January 14, 1784, can probably be assigned with reasonable certainty to that city.

Peter Maverick bore a surname which had long been a part of America's history, although there is little reason to believe that he was aware of the fact. His children and nephews a generation later apparently had a vague and completely erroneous idea that their grandfather Maverick had come "to this country from England, about the year 1774, when but eight or ten years of age." They suspected that the New York Mavericks had some connection with the Boston Mavericks but they could not establish the link, even when they understood that a legacy in the Bank of England was somehow at stake.

Sometime later, in 1894, a report in the New England Historical and Genealogical Register proved their suspicions to be correct; records published by the same journal in 1942 and 1943 for the first time made generally available the genealogical ramifications of the Massachusetts Maverick family.

The known genealogical line begins with a certain Robert Maverick of Devonshire who had a son Peter, a clergyman who flourished in the early years of Elizabeth's reign. Among his children was a Reverend John Maverick, baptized November 28, 1578, who went to Exeter College at Oxford in 1595, receiving his degree of Bachelor of Arts in 1599 and Master of Arts in 1603.

He served his church in Devonshire for years, and then in 1630 sailed with several of his family for Massachusetts, arriving at Hull on May 30 and proceeding thence to Dorchester. A year later he took the freeman's oath, and he lived as a colonist and leader of his church until his death in 1637, to be followed in that leadership by Richard, the first of Mathers.

Although Reverend John Maverick was the founder of the family in America, he was not the first of that family to arrive in this country. His young son Samuel had left England six years earlier and had settled on an island in Massachusetts Bay. In the new country he began a stormy career as a defender of the British crown against colonial discontent, a career which gave him the title of Loyalist, brought him an appointment as King's Commissioner, and earned him finally a royal gift of a house and lot at what is now 50 Broadway in New York.

There may have been another son of John, bearing his father's name, who went to the Barbadoes and later in life to the colony of Carolina, there to found the American family of Mavericks who have long been prominent in the South. That this John was a son of Reverend John, and a brother of Samuel the Loyalist, is entirely plausible, but careful genealogists seem unwilling to say that the link is established.

But our chief concern is with Elias, another son of Reverend John. Elias' marriage to Anne Harris in 1633 brought him five sons and six daughters. Paul, one of these children, married Jemimah, the daughter of Lieutenant John Smith. Paul and Jemimah were the parents of the John Maverick who became an importer of hard woods in Middle (now Hanover) Street in Boston, at the sign of the Cabinet and Chest of Drawers. Probably the most famous Boston Maverick was Samuel, the grandson of this John, who as a boy was killed in the Boston massacre. But it is John's son Andrew, the father of Peter Rushton Maverick, who attracts our particular attention.

Andrew was born in Boston February 4, 1729, and baptized five days later. How and where he spent the first twenty-four years of his life is unknown, but in 1753 we find him in New York City, where on July 17 he was admitted as a freeman. On March 28 of the following year he married eighteen-year-old Sarah Rushton, the daughter of the prosperous mason Peter Rushton, and four years later, on March 13, 1759, he joined Captain Tobias Van Zandt's company of New York militia. His occupation has been given by one writer as "painter," by another as "artist," but when he was admitted as a freeman and when he joined the militia, he himself designated his occupation as "painter." Except for a self-portrait which has been mentioned as his work, there appears to be little reason to consider him a worker in the fine arts.

There is one more record of Andrew before he slips from view in the obscurity of the scarce and poorly kept pre-Revolutionary records. In 1760, after George the Second died in England, the American colony elected a new assembly to represent the people to his young successor, George the Third. In New York City, there were six candidates, two of whom, James DeLancey and William Bayard, were eager to give the young king the same loyalty that they had given so profitably to his predecessor, while the other four, who were of the Whig or Patriot Party, represented the fast-growing national sentiment that was to bring revolt fifteen years later. During the three days of polling, in February of 1761, Andrew Maverick recorded his vote for the Patriots, Philip Livingston, William Cruger, John M. Scott, and Leonard Lispenard. Although Andrew did not live to see his only son, Peter Rushton Maverick, grow up, he left him this and other examples of independent thinking which the son was to follow energetically.

The early years of Peter Rushton Maverick are little illuminated by records, beyond that of his birth on April 11, 1755, and the death of his mother four years later. When the boy was ten, his grandfather Rushton made a will in which he left all his estate, including "houses, lands, bonds, slaves," to his wife Bethiah during her widowhood, but after her death the whole was to go to "my grandson Peter Rushton Maverick." From this and other provisions in the will it appears that Peter was not only an only child of his parents but also an only grandchild of the Rushtons, and the fact that no mention was made of Andrew may be the basis for the belief that he died before Peter's tenth birthday.

Two years after making this will the grandfather died. Bethiah lived on for twenty-three years longer, to see her grandson well established as an engraver and her great-grandson beginning his young apprenticeship. There appears to be no further record of the transfer of the family property to Maverick. Years afterward, however, when he sold the Rushton Liberty Street lot to the Quakers for a meeting house, he claimed his title to it as the "grandson and only heir" of Peter Rushton.

On July 4, 1772, the day not yet being a national holiday, seventeen-year-old Peter Rushton Maverick and nineteen-year-old Ann Reynolds posted bond with the secretary of the Province of New York and received a license to wed. Three years later, on Sunday, April 23, 1775, word of the battles of Concord and Lexington reached New York late in the day. Within forty-eight hours the royal arsenal had been sacked by the revolutionary mob and arms distributed among the revolutionary citizens. Peter, now a father as well as a husband, received a firelock, bayonet, belt, and other equipment; when he signed the receipt he wrote, as if in realization of the importance of the occasion, his full name, "Peter Rushton Maverick."

By midsummer, apparently to equip an organized body of militia, the weapons issued to the willing young men were recalled; and Maverick, described as a silversmith of Batteau (Dey) Street, was credited with Musket No. 543. This record gives us two bits of knowledge. It gives us Maverick's address nine years before the announcement in 1784 of his business in Crown Street. More important, it proves that Maverick was already established in his craft before the Revolution. The knowledge is not surprising, for an apt young man was scarcely likely to have been untrained at twenty, and he was, moreover, a man of family — baby Sarah was now a year and a half old, and another child was expected in the approaching winter.

Nearly a century ago the story was first recorded in print, without documentation, that by August of 1775 he was an ensign in Captain M. Minthorn's company of John Jay's Second Regiment of New York Militia, but there appears to be no official record. However, in 1789 after the Revolution had ended and the new nation had begun, the somewhat more mature Peter Rushton Maverick was listed as an ensign in Lieutenant Colonel James Alner's regiment, and four years later, in 1793, his title had become lieutenant.

When Rebecca, the second daughter of the Peter Rushton Mavericks, was born on January 8, 1776, New York was in constant threat of attack by the British. By 1778, the city was in the hands of the British Army, and about half of the population had fled to the Jerseys or to that part of New York above the Harlem River. Some of those who remained in the city stayed because they could not get away; many others stayed because their sympathies were with the established government. Did the Mavericks flee from New York at the threat of British attack? No record tells us, but, with a wife and two children to care for, it is hardly likely that Maverick would remain and risk British captivity.

Although three children were born to the Mavericks before the British evacuated New York in 1783, their places of birth are not recorded, and thus we have little or no clue as to the whereabouts of the family. We do know that a girl Ann was born on December 3, 1778, and a boy Peter was born October 22, 1780, and another boy Andrew on May 26, 1782. If the Mavericks were among the refugees from New York, then they must have returned very soon after the British left; the birthplace of a sixth child, Maria, who was born on January 14, 1784, can probably be assigned with reasonable certainty to that city.

The Young Engraver

One small indication that Peter Maverick was recognized as an engraver in his own right very soon after the publication of his Adam and Eve engraving is to be found in his father's change in signature about this time. In his early work in the 1780's, Peter Rushton Maverick most commonly signed his engravings merely "Maverick," but in the dated work of the 1790's we frequently find "P. R." or "Peter R. Maverick," as if he had begun to recognize that he should leave the simple "Peter Maverick" for the son who had no middle name. The same tendency to include the use of his middle initial is also evident in early city directories and in advertisements. From the first directory in 1786 to that of 1792, he uses the signature "Peter Maverick," but from 1793 to his death he added his middle initial. The intent seems clear: a recognition that his twelve-year-old son should have the distinction of a separate nomenclatural niche.

The work of young Peter in the Adam and Eve picture was quite different from the type of work which was to make him famous; the early work was a relief block, in which the surface not intended for printing was carved away, but his fame as a craftsman depends on his intaglio work, where the design to be printed was cut on a polished copperplate, and the parts to be white in the finished print were left untouched. Since the Maverick shop was not seriously concerned with relief blocks, we may be sure that a nine-year-old boy so familiar with the burin must have begun very early to work on copper.

Probably one of the first tasks undertaken by Peter was that of polishing plates. Perhaps no better training could be devised to impress the beginner with a respect for the prepared plate than to require him to prepare his own. Not only must the polisher rub the plate with pumice or a fine abrasive until it is clear, shiny, and mirror-like, he must make it so smooth that not the slightest bit of sticky oily ink can resist being wiped away, so smooth that uncut parts of the plate, after inking and wiping, will not soil white paper. Occasional dabblers in engraving would have this done by a silversmith's assistant who did polishing in his spare time. One such man, mentioned in Alexander Anderson's diary and known to us only as "a Swede," received $1.15 for the labor alone of polishing a plate about six inches square, and $1.35 for one slightly larger. Considering the price of labor at that time, it must have been slow, tedious work to command such amounts. But considering also the type of father Peter had, we can scarcely believe that the boy did not polish many plates before he had an assistant to do it for him.

When the plate was properly polished, it was ready for the transfer of the design and for cutting. The burin (in one of its various forms) which was used in cutting the relief block was also used to produce the intaglio plate, but in the case of the relief block it was used to cut away all but the lines of the design, whereas in the case of the intaglio plate it was used to cut the lines; for it is the furrow which the tiny plow cuts, or which the acid eats, that is printed in this latter method, not the metal between. Peter also had to learn that in intaglio work he could not print a black surface as he had in the background of his signature in the Adam and Eve print. In line engraving there is no such thing as a plain black surface; if an area of metal were to be cut away, the ink would fill it but the wiping would empty it, and the print would show only the edges. So Peter had to learn to think of his dark areas in the picture as lines—lines spaced very close and yet not merging, or lines crossed at various angles—and his lighter areas as lighter lines or more widely spaced lines, or both. [Some of these statements do not apply to stipple work, which Peter did masterfully, but the nature of engraving will perhaps be better understood if one process is considered at a time.] The control of these factors, the spacing of the lines and the thickness of the line itself, continued to be a part of Peter's learning during his whole career. Though mechanical devices were later developed to make this control more exact, yet his eye and hand, and the brain where even manual skill resides, never surrendered to a machine.

We may be sure that Peter also learned very early to print his plates, for this shop was equipped to do so, though it was the custom for some engravers to employ other shops for their printing, or simply to furnish the plate to the customer, who would then find his own printer. The process of printing is essentially simple, but like many other simple processes demands that much be mastered before an expert product results. Peter had to learn how to spread an oily ink over the whole surface with a dauber, which must then be wiped off—at least all that would wipe off—first with a cloth and then with the whiting-covered palm of the hand, leaving ink only in the lines cut into the polished surface. He then had to warm the plate sufficiently to ensure the softening of the ink in all the lines, place it face up on the bed of his press, place over it a sheet of paper (dampened so that pressure would force it down into the grooves to receive the ink), and squeeze paper and plate under powerful rollers turned by long spoke-like handles. To turn the wheel, if the press was tight or the padding over the plate was thick, the boy must have had to climb those spokes like a monkey. [This type of press is shown on the Samuel Maverick trade card engraved (1813-1817) by Peter.] But when the powerful pressure had pushed the softened paper into every channel of ink, no matter how delicate the line, the sheet of paper which Peter peeled off the copper surface must have seemed worth the labor. Something, at least, must have kept him at it through years of drudgery, and the skill which his first signed work shows, ten years later, would indicate that one force that kept him at work was his own successful progress.

The engraving of the shop during this period of Peter's youth continued to be various, and it appears that at about this time a new type of work was added which was to become of great importance. This was bank-note engraving. Early paper money was commonly printed from type, and depended commonly for its safety upon the rarity of printing equipment, upon elaborate type designs, and upon such warnings as "Death to counterfeit" printed upon it. But as printing presses and capable printers became more common, and the threat of death proved too weak a deterrent, a premium was placed on devices to make harder the task of the unauthorized reproducer of currency. The skillful engraver had a powerful device in his own skill, of course, and as time went on he added elements to his pattern to increase the challenge to the copyist. We find these elements in the earliest notes bearing the Maverick name. These early notes contained, in their simplest form, the elaborately lettered promise of the bank to pay either a stated amount or an amount to be inserted in ink, spaces for signatures, and pictorial designs related to the history or the location or the name of the bank. In some also we find the early use of panels containing the engraved or inserted figures for the denomination of the note. These panels were blocks of parallel lines, serving much the same purpose as devices for check protection serve today. As machine controls were created, the lines were more accurately spaced, or the variations in spacing achieved an effect resembling moire silk.

But a craftsman's shop was not only a business establishment, it was also a training school. At No. 3 Crown Street and at No. 65 Liberty Street [The name Crown Street finally gave way to the new name Liberty Street. Tradition persists that the elder Maverick was a chief factor in the change of name, that he even offered to pay out of his own pocket the expense of changing the street signs.], where the Mavericks moved in 1794, Peter must have been in daily contact with many whose names were to become important ones in the graphic arts. One of these was William Dunlap, painter, theatrical producer, and historian of both arts, who in 1787-88 put himself under Peter Rushton Maverick's tutelage to learn "the theory and practice of etching." [I have avoided, throughout this volume, the use of the word "etching," since it is perhaps best reserved for the complete wax-and-acid methods. Alexander Anderson, in the 1790's, records the following formula for etching varnish: "wax, black pitch, and Burgundy pitch," and that of one of the Tiebouts as "wax and rosin." Although Peter Maverick used acid for stipple and for etching in the rotary lathe engraving processes developed by him and the Durands in Newark, the inventory of his richly stocked shop at the time of his death shows no wax, acid, or other material that would indicate his use of acid for cutting line.] Many persons consider it also likely that Benjamin R. Tanner, later prominent in Philadelphia, learned his engraving under Maverick. Francis Kearny, who was to follow Tanner to Philadelphia after beginning his famous career in New York, is recorded as Maverick's apprentice from 1798 on. Kearny was near Peter Maverick's age, and the two young men worked together for years. And there must have been many others whose training, or partial training, touched this shop in Crown or Liberty Street. In the next quarter of a century five copperplate printers by the name of Reynolds were in New York at various times; it would be strange if some of them were not maternal relatives of Peter's who had learned the trade in the elder Maverick's shop.

A more important possibility flickers enticingly through the mist of a century and a half: Alexander Anderson may well have got his start as an engraver from his contacts with Maverick; a formal apprenticeship seems unlikely, for he was first apprenticed, against his will, to a doctor. In his old age, Anderson said that in the procession to honor the adoption of the new federal constitution, on July 23, 1788, he walked with the elder Maverick, and that Maverick was then the only engraver in New York. This is a long-remembered detail; it is incorrect at least in respect to Maverick's uniqueness in the field, but it may point to an early Maverick inspiration if not specific instruction. Anderson was thirteen at the time; seven years later he was a licensed physician in charge of Bellevue Hospital during a yellow-fever epidemic, but shortly afterward he renounced medicine for the stronger claim of engraving, an art which was to bring him a long career and the title of America's first engraver in wood.

Another influence which was strong in this decade in the Maverick shop and residence was Peter Rushton Maverick's ardor for the new nation and for the opportunity it gave for new freedom of thought. Very early, however, and probably from the beginning, his enthusiasm was not of a piece with that of some of the new American aristocrats who brought him their coats of arms to engrave. It went further than theirs, and embraced the hopes of the group calling themselves Republicans, who shortly accepted the leadership of Thomas Jefferson, refused to take too seriously the many loud and sweeping denunciations of the French Revolution, looked to reason as a worthy source of enlightenment, and fought everything, fundamental or trivial, that smacked of aristocracy and monarchy. For the Republican Society of this time Maverick made a bookplate, and its motto, "Mutual Improvement," epitomizes this new belief that the mass of mankind could lift itself by its own collective bootstraps instead of waiting until someone might think to throw down a rope.

Peter R. Maverick's espousal of this attitude in political matters was only a moderately bold act, but in respect to religious questions he went still further, as he sought to find the answers in intellect and reason. His most public manifestation of this quest was in his association with the poet Freneau and with John Lamb in the interests of deism. When this group sponsored an address by Elihu Palmer, the deist leader, and petitioned the Common Council for the use of the City Hall courtroom on July 4, 1797, the petition was rejected, and alongside Palmer's name a clerk inserted the label "infidel." Three years later the group gave support to a short-lived weekly The Temple of Reason, which stirred the opposition of the devout and which embarrassed Jefferson's Republicans by forcing them to defend themselves against charges of enmity to religion.

Maverick's position in respect to political and religious thinking brought him into contact with the aged Thomas Paine, when that patriot, after defending humanity's cause as a citizen in three great nations, came back to die in the land of his last remaining citizenship, only to see that citizenship revoked and the masses for whom he had labored turn against him. A letter pasted in a scrapbook by Maverick's grandson nearly a century ago and recently discovered by two great-great-granddaughters gives evidence of Thomas Paine's straits, and of Peter Rushton Maverick's attempts to help. It reads:

One small indication that Peter Maverick was recognized as an engraver in his own right very soon after the publication of his Adam and Eve engraving is to be found in his father's change in signature about this time. In his early work in the 1780's, Peter Rushton Maverick most commonly signed his engravings merely "Maverick," but in the dated work of the 1790's we frequently find "P. R." or "Peter R. Maverick," as if he had begun to recognize that he should leave the simple "Peter Maverick" for the son who had no middle name. The same tendency to include the use of his middle initial is also evident in early city directories and in advertisements. From the first directory in 1786 to that of 1792, he uses the signature "Peter Maverick," but from 1793 to his death he added his middle initial. The intent seems clear: a recognition that his twelve-year-old son should have the distinction of a separate nomenclatural niche.

The work of young Peter in the Adam and Eve picture was quite different from the type of work which was to make him famous; the early work was a relief block, in which the surface not intended for printing was carved away, but his fame as a craftsman depends on his intaglio work, where the design to be printed was cut on a polished copperplate, and the parts to be white in the finished print were left untouched. Since the Maverick shop was not seriously concerned with relief blocks, we may be sure that a nine-year-old boy so familiar with the burin must have begun very early to work on copper.

Probably one of the first tasks undertaken by Peter was that of polishing plates. Perhaps no better training could be devised to impress the beginner with a respect for the prepared plate than to require him to prepare his own. Not only must the polisher rub the plate with pumice or a fine abrasive until it is clear, shiny, and mirror-like, he must make it so smooth that not the slightest bit of sticky oily ink can resist being wiped away, so smooth that uncut parts of the plate, after inking and wiping, will not soil white paper. Occasional dabblers in engraving would have this done by a silversmith's assistant who did polishing in his spare time. One such man, mentioned in Alexander Anderson's diary and known to us only as "a Swede," received $1.15 for the labor alone of polishing a plate about six inches square, and $1.35 for one slightly larger. Considering the price of labor at that time, it must have been slow, tedious work to command such amounts. But considering also the type of father Peter had, we can scarcely believe that the boy did not polish many plates before he had an assistant to do it for him.

When the plate was properly polished, it was ready for the transfer of the design and for cutting. The burin (in one of its various forms) which was used in cutting the relief block was also used to produce the intaglio plate, but in the case of the relief block it was used to cut away all but the lines of the design, whereas in the case of the intaglio plate it was used to cut the lines; for it is the furrow which the tiny plow cuts, or which the acid eats, that is printed in this latter method, not the metal between. Peter also had to learn that in intaglio work he could not print a black surface as he had in the background of his signature in the Adam and Eve print. In line engraving there is no such thing as a plain black surface; if an area of metal were to be cut away, the ink would fill it but the wiping would empty it, and the print would show only the edges. So Peter had to learn to think of his dark areas in the picture as lines—lines spaced very close and yet not merging, or lines crossed at various angles—and his lighter areas as lighter lines or more widely spaced lines, or both. [Some of these statements do not apply to stipple work, which Peter did masterfully, but the nature of engraving will perhaps be better understood if one process is considered at a time.] The control of these factors, the spacing of the lines and the thickness of the line itself, continued to be a part of Peter's learning during his whole career. Though mechanical devices were later developed to make this control more exact, yet his eye and hand, and the brain where even manual skill resides, never surrendered to a machine.

We may be sure that Peter also learned very early to print his plates, for this shop was equipped to do so, though it was the custom for some engravers to employ other shops for their printing, or simply to furnish the plate to the customer, who would then find his own printer. The process of printing is essentially simple, but like many other simple processes demands that much be mastered before an expert product results. Peter had to learn how to spread an oily ink over the whole surface with a dauber, which must then be wiped off—at least all that would wipe off—first with a cloth and then with the whiting-covered palm of the hand, leaving ink only in the lines cut into the polished surface. He then had to warm the plate sufficiently to ensure the softening of the ink in all the lines, place it face up on the bed of his press, place over it a sheet of paper (dampened so that pressure would force it down into the grooves to receive the ink), and squeeze paper and plate under powerful rollers turned by long spoke-like handles. To turn the wheel, if the press was tight or the padding over the plate was thick, the boy must have had to climb those spokes like a monkey. [This type of press is shown on the Samuel Maverick trade card engraved (1813-1817) by Peter.] But when the powerful pressure had pushed the softened paper into every channel of ink, no matter how delicate the line, the sheet of paper which Peter peeled off the copper surface must have seemed worth the labor. Something, at least, must have kept him at it through years of drudgery, and the skill which his first signed work shows, ten years later, would indicate that one force that kept him at work was his own successful progress.

The engraving of the shop during this period of Peter's youth continued to be various, and it appears that at about this time a new type of work was added which was to become of great importance. This was bank-note engraving. Early paper money was commonly printed from type, and depended commonly for its safety upon the rarity of printing equipment, upon elaborate type designs, and upon such warnings as "Death to counterfeit" printed upon it. But as printing presses and capable printers became more common, and the threat of death proved too weak a deterrent, a premium was placed on devices to make harder the task of the unauthorized reproducer of currency. The skillful engraver had a powerful device in his own skill, of course, and as time went on he added elements to his pattern to increase the challenge to the copyist. We find these elements in the earliest notes bearing the Maverick name. These early notes contained, in their simplest form, the elaborately lettered promise of the bank to pay either a stated amount or an amount to be inserted in ink, spaces for signatures, and pictorial designs related to the history or the location or the name of the bank. In some also we find the early use of panels containing the engraved or inserted figures for the denomination of the note. These panels were blocks of parallel lines, serving much the same purpose as devices for check protection serve today. As machine controls were created, the lines were more accurately spaced, or the variations in spacing achieved an effect resembling moire silk.

But a craftsman's shop was not only a business establishment, it was also a training school. At No. 3 Crown Street and at No. 65 Liberty Street [The name Crown Street finally gave way to the new name Liberty Street. Tradition persists that the elder Maverick was a chief factor in the change of name, that he even offered to pay out of his own pocket the expense of changing the street signs.], where the Mavericks moved in 1794, Peter must have been in daily contact with many whose names were to become important ones in the graphic arts. One of these was William Dunlap, painter, theatrical producer, and historian of both arts, who in 1787-88 put himself under Peter Rushton Maverick's tutelage to learn "the theory and practice of etching." [I have avoided, throughout this volume, the use of the word "etching," since it is perhaps best reserved for the complete wax-and-acid methods. Alexander Anderson, in the 1790's, records the following formula for etching varnish: "wax, black pitch, and Burgundy pitch," and that of one of the Tiebouts as "wax and rosin." Although Peter Maverick used acid for stipple and for etching in the rotary lathe engraving processes developed by him and the Durands in Newark, the inventory of his richly stocked shop at the time of his death shows no wax, acid, or other material that would indicate his use of acid for cutting line.] Many persons consider it also likely that Benjamin R. Tanner, later prominent in Philadelphia, learned his engraving under Maverick. Francis Kearny, who was to follow Tanner to Philadelphia after beginning his famous career in New York, is recorded as Maverick's apprentice from 1798 on. Kearny was near Peter Maverick's age, and the two young men worked together for years. And there must have been many others whose training, or partial training, touched this shop in Crown or Liberty Street. In the next quarter of a century five copperplate printers by the name of Reynolds were in New York at various times; it would be strange if some of them were not maternal relatives of Peter's who had learned the trade in the elder Maverick's shop.

A more important possibility flickers enticingly through the mist of a century and a half: Alexander Anderson may well have got his start as an engraver from his contacts with Maverick; a formal apprenticeship seems unlikely, for he was first apprenticed, against his will, to a doctor. In his old age, Anderson said that in the procession to honor the adoption of the new federal constitution, on July 23, 1788, he walked with the elder Maverick, and that Maverick was then the only engraver in New York. This is a long-remembered detail; it is incorrect at least in respect to Maverick's uniqueness in the field, but it may point to an early Maverick inspiration if not specific instruction. Anderson was thirteen at the time; seven years later he was a licensed physician in charge of Bellevue Hospital during a yellow-fever epidemic, but shortly afterward he renounced medicine for the stronger claim of engraving, an art which was to bring him a long career and the title of America's first engraver in wood.

Another influence which was strong in this decade in the Maverick shop and residence was Peter Rushton Maverick's ardor for the new nation and for the opportunity it gave for new freedom of thought. Very early, however, and probably from the beginning, his enthusiasm was not of a piece with that of some of the new American aristocrats who brought him their coats of arms to engrave. It went further than theirs, and embraced the hopes of the group calling themselves Republicans, who shortly accepted the leadership of Thomas Jefferson, refused to take too seriously the many loud and sweeping denunciations of the French Revolution, looked to reason as a worthy source of enlightenment, and fought everything, fundamental or trivial, that smacked of aristocracy and monarchy. For the Republican Society of this time Maverick made a bookplate, and its motto, "Mutual Improvement," epitomizes this new belief that the mass of mankind could lift itself by its own collective bootstraps instead of waiting until someone might think to throw down a rope.

Peter R. Maverick's espousal of this attitude in political matters was only a moderately bold act, but in respect to religious questions he went still further, as he sought to find the answers in intellect and reason. His most public manifestation of this quest was in his association with the poet Freneau and with John Lamb in the interests of deism. When this group sponsored an address by Elihu Palmer, the deist leader, and petitioned the Common Council for the use of the City Hall courtroom on July 4, 1797, the petition was rejected, and alongside Palmer's name a clerk inserted the label "infidel." Three years later the group gave support to a short-lived weekly The Temple of Reason, which stirred the opposition of the devout and which embarrassed Jefferson's Republicans by forcing them to defend themselves against charges of enmity to religion.

Maverick's position in respect to political and religious thinking brought him into contact with the aged Thomas Paine, when that patriot, after defending humanity's cause as a citizen in three great nations, came back to die in the land of his last remaining citizenship, only to see that citizenship revoked and the masses for whom he had labored turn against him. A letter pasted in a scrapbook by Maverick's grandson nearly a century ago and recently discovered by two great-great-granddaughters gives evidence of Thomas Paine's straits, and of Peter Rushton Maverick's attempts to help. It reads:

Tuesday

Friend Maverick

I send the dollar I owe you and am much obliged to you. I will return your bed and pillows. They are both on my cot. John sleeps on my own bed in the passage. I did not know that the straw bed was destroyed. When I fixed up my cot, the straw bed made it too high which was the reason it was put away and no care, I find, was taken of it.

I send the dollar I owe you and am much obliged to you. I will return your bed and pillows. They are both on my cot. John sleeps on my own bed in the passage. I did not know that the straw bed was destroyed. When I fixed up my cot, the straw bed made it too high which was the reason it was put away and no care, I find, was taken of it.

Thomas Paine

I am going tomorrow to look at some rooms at Mr. Jervis [sic] the painter as Hitt's rooms are not yet ready.

[Paine, after leaving William Carver's on November 3, went to live with John Wesley Jarvis in early November of 1806, and the letter was apparently written just before this time. Hitt is probably John Hitt, the baker in Broome Street from whom Paine later rented a room. As to John who slept in the passage, I know of no clues that warrant anything weightier than a guess, but it is a pleasant guess that friendly John Fellows had given temporary shelter in his own lodgings to the old Patriot, and that Maverick had aided in the emergency with the loan of his pillows and mattresses, and the dollar.]

But where young Peter stood on these matters of politics and religion we cannot say, for he held himself close to his engraving business. His name is not to be found tied to any causes; he is not listed in church or lodge records. His father and later his two brothers were active as volunteer firemen; his grandfather, father, and his brother Andrew joined the militia; and his father, brother, and nephew were members of the Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen. But Peter's name does not appear in connection with any of these organizations; it would seem that he was only interested in those directly connected with his professional life.

We know little of Peter's own mother, Ann Maverick, who died in 1787. Her place was taken the next year by her sister, Rebecca, who lived long and has left a fairly clear impression of what she must have been like as a mother to Samuel and stepmother to Sarah, Rebecca, Ann, Peter, Andrew, and Maria. [Elizabeth, Ann's seventh child, apparently did not survive infancy.] She it was who during the British occupation of New York City was pursued across Kingsbridge by Tory guerrillas. From her later business career as a widow she seems to have been shrewd, practical, and somewhat domineering. She dressed smartly and, so her children and grandchildren sometimes thought, a little garishly. She was "always a very devout person," said one who knew her from the beginning of her widowhood. The most educated, perhaps, of all the people of her acquaintance considered her "a person not endowed with a very high order of intellect," but several less literate observers spoke of her brilliance, her keen interest in history and current happenings, her ability to converse about literature. She must have been a force in the family during her husband's life, for she obviously held the reins in her hands through her long widowhood, in spite of the fact that she could read only a little and could not write even her name.

The first of the children to leave home was Sarah, who on May 10, 1792, at the age of eighteen, married Benjamin Montanye, son of Peter Montanye, in the Reformed Protestant Dutch Church of New York City. On May 27, five years later, in the same church, Rebecca, aged twenty-one, married James Woodham, and Ann, aged eighteen, became the wife of Patrick Munn. Peter was now the oldest child left at home with Andrew and Maria and his half-brother Samuel. Andrew was old enough to be helping in the shop, and Samuel was probably around the shop as something less than a help.

Soon after these marriages, the family was again forced to flee for refuge outside the city, this time before a force more terrible than the invading British Army, the deadly yellow fever. Several times during the 1790's it struck; at one time a crude quarantine was enforced by a board fence across the island of Manhattan on the line of Liberty Street. Pedlars drove through the streets crying their wares, "Coffins! All sizes of coffins!" All who could escape from the pest-ridden city did so, and many a shop was left in charge of a single employee to serve what little business there was.

At 65 Liberty Street one young man was so left in the great epidemic which began in the summer of 1798. Carrying on the work of the shop, he also helped nurse a sick friend, only to be stricken with the fever himself and to lie sick and alone. Many years later, Grant Thorburn, brother of the sick friend, told of making the rounds of all the young men who had fallen ill while befriending his brother. He reported that all of these men, stricken in late August, "had got better or died" by September 22, but he gave no clue as to which fate befell the young man at 65 Liberty Street, or who the young man was. He may have been a hired employee, perhaps the anonymous "male adult" listed as a member of the household in the 1790 census. Or he may have been a member of the immediate family, and, if so, he may have been the eldest boy, Peter, a competent workman and manager by this time.